I waited patiently for the rolling cumulonimbus clouds to run out of tears before I frog leaped across the street. Dodging pools of rain captured in cement bowls and 1950’s General Motors automobile shells run on Toyota engines, I made it across the avenue. My friend Michael pointed at a small cafe. “The best sandwiches.”, he professed with his ninth visit to Havana knowledge as he scampered up the block out of the storm. I ducked into the quiet cafe and chose a seat at the bar. It was relatively empty but a few customers finishing their drinks. A middle-aged woman approached from the other side of the counter and asked what I’d like in her distinctly Cuban Spanish. I make it a point to memorize enough of the language to always successfully order. “Me gustaría tener un sandwich cubano y un mojito por favor”, stumbled out of my mouth as she scribbled on a piece of scrap paper. The Cuban sandwich I just ordered wasn’t particularly native. In fact, the historians credit a Tampa Florida cigar factory for its origin. The sando later migrated back to its namesake country in the late 1800’s when travel from the United States was both easy and frequent. Not something my lifetime can remember, until now…maybe.

The above represents a visual journey of this story.

The mojito came first, patiently and dexterously made by the older man who seemed to run the cafe. The Cubano wasn’t far behind, served by a third worker who appeared from the back room. The bread was incredibly fresh, something I’d come to learn is one of the simplistic staples of Cuban culture. The ham and pork were conservative but delicious. It was fresh, even the ham, seemingly chemical free. I ate in silence stopping every few moments for a sip of my cocktail. Time moved slow and I savored my bites.

Is this paradise or prison?

It was my third day in Havana and I had already learned a lot about Cuban culture. The sandwich and cafe seemed to echo much of those lessons. I found myself stuck contemplating a thought that would turn out to be a common conundrum for me over the span of my 10 days in Cuba. “Is this paradise or prison?”, I asked my conscience. I wouldn’t learn the answer to that question for another 7 days.

Cuba sticks to you

I’ve been talking about this trip since I landed back on US soil. Nothing has been the same for me since I experienced this most foreign of lands. That implies some mind altering event took place or I experienced something that forever changed my trajectory in life. Neither are true. What I came back with was an itching wonder of the future based on a trip back to the past. Not just Cuban people’s future but my own and, more importantly, the non-socialist population of the world.

Over the next few paragraphs, I’ll attempt to break down Cuban history and culture through the journey that was my 10 days in country. It won’t begin to complete the circle of knowledge that I just cracked open but I hope it starts to give you some non-media perspective into a country that is undergoing unprecedented change. The compass for this education turned out to be Cuban food. Starting with that Cuban sandwich and meandering through food lines, paladors and locals homes, the satiation to my curiosity was never that far from something to eat.

Early morning in Centro Habana

Coveted Cuban Visa

Michael, the friend who directed me to the sandwich cafe, invited me to tag along on his Cuba adventure. His company, Photo Workshop Adventures, helps small groups of photo enthusiasts explore the most photogenic cities in the world while enjoying luxury accommodations, transportation and culinary excellence. It also covers the much misunderstood Cuban visa providing me with a 10-day people-to-people cultural visa. Cuba, as he told me and the rest of the group from the beginning, is the anomaly to the rest of his tour destinations. “Please remember to bring your sense of adventure” our pre-trip dossier read. My excitement was redlining. Not only was I psyched to spend a week with camera in hand, something I had not done in a decade, but this was high on my gastro-travel hit list. I was finally going to explore Cuban cuisine from the right side of the border.

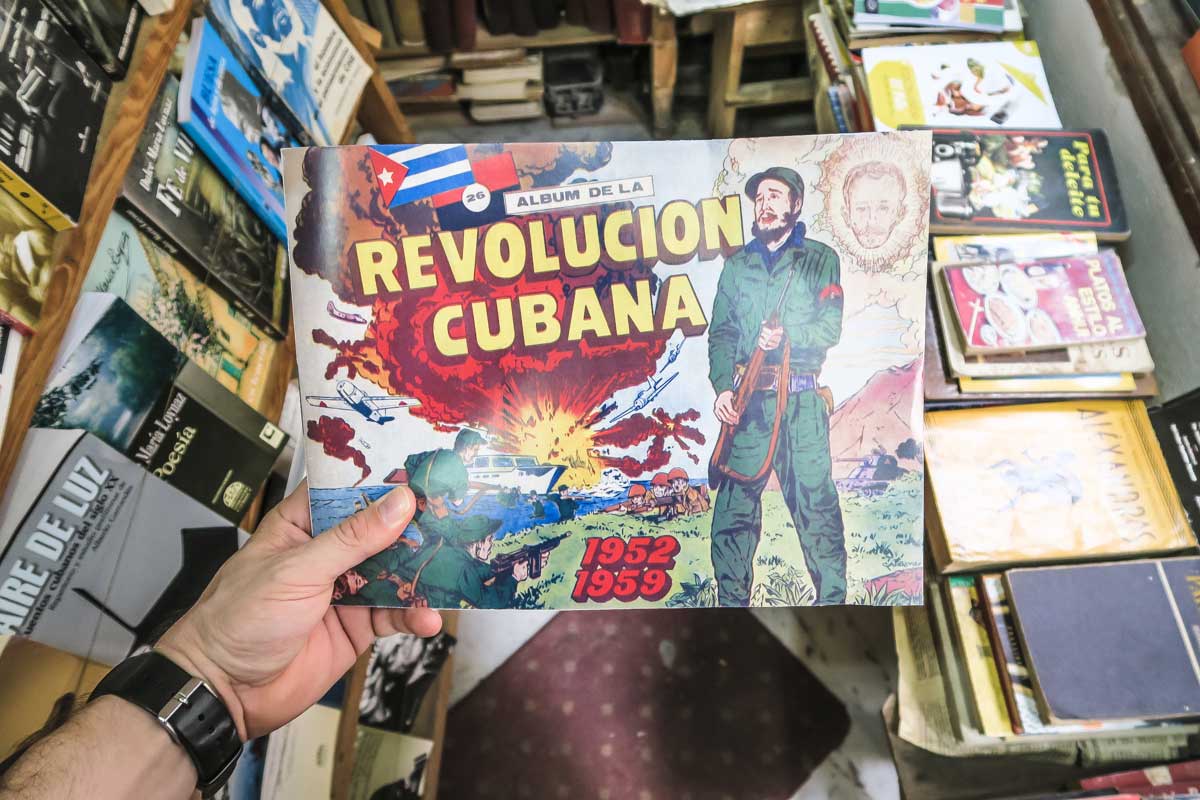

Notorious Past

My immediate observation of Cuba was that you could blatantly see it’s notorious past. Both parts of that statement are often exaggerated and misused, so I feel the need to quantify. Notorious, known for something bad, from an American perspective that is. Standing on a single corner you could absorb the Italian mafia’s hey day of the 40’s and 50’s, see the revolution and communist regime of Fidel Castro, observe his relationship with the Soviet Union during the cold war, watch the fall of the iron curtain, contemplate the immediate end of monetary and political support to the Cubans in the 90’s, imagine rafts of Cuban’s attempting a 90 mile float across the gulf of Mexico, detect the Chinese aid that dried up when they realized monetary return was nil, then, return to the moment just before now, a tired military state running a dysfunctional government with a country of hard working civilians that have been closed off to the rest of the worlds progression for the last 60 years. Blatantly in that the cacophony of decrepit art deco hotels, derelict 1950’s cars and Russian transport trucks were peppered up and down every street.

Montage of Cuban vehicles

Impending future

When you look in the opposite direction of the past you see a very hazy future. The end of what looks like a Castro-run Cuba, public wifi in the streets (yet still government controlled), cruise ships in Old Havana bay (although not yet American), a few luxury good stores (mostly for those tourists) and restaurants (paladors) with professional kitchens and chefs ready to serve patrons like a 3 star establishment in the US and Europe, come into focus with each passing day. The media will have us believe that Cuba’s change will happen over the course of months not years or even decades. The tourists have taken the bait and started making their way not just to Havana but through out the country to get a “taste” before the changes sweep away the historic beauty the last 60 years created. This creates an incredible strain on a fragile infrastructure.

This results in stress cracks that show their imperfections at the worst times.

For 6 decades Cuba didn’t need systems in place to handle 1000’s of tourists arriving each week, sleeping, eating and exploring their cities and towns. This results in stress cracks that show their imperfections at the worst times (as far as traveling goes). Such as us arriving from a day of travel to learn that our hotel is triple booked and we need to travel across town where they “think” we’ll have a room. The honest reality is Cuba has a big upgrade in their future if they want to handle the tourist crowd and keep them coming back. If they don’t, traveling to the island will be more like happening upon a car crash. Drive by, get a good look, don’t stay too long and move on.

Non-American cruise ship in Havana harbor.

Embracing Creativity

Liu was our government appointed tour guide. This is a mandatory requirement for all tourists to Cuba. I spent the entire ten days with her. Much of it walking the streets or riding a bus. By the end, she was not a tour guide but a friend.

Liu bookended by Larry and Jamie. Two other friends I met on the trip.

This fast friendship happened many times on the trip. I sipped cocktails with painters, jammed with musicians, spoke with rappers, shot with photographers and ate with historians. Although I only spent a few hours with each of them, many of the meetings were in their homes or over a meal or cocktail. Which is to say, relaxed, comfortable and familiar feeling. All were introductions through Michael who had strong, and frequent, interactions with each of them. This was an invaluable part of the trip. The ability to speak so intimately and candidly with so many locals allowed me to understand what Cuban culture is like and what the people of this country love, hate and hope changes.

One of the most surprising lessons from the aforementioned creatives was the embracing and allowance of artistic expression by the government regime. For all the rules and control, the arts were seemingly unbridled and quite literally everywhere you looked. It was at this moment that I realized the only art not blooming from the cracks and crevices of every decrepit, unkept building was the culinary arts.

View from above a palador in Cienfuegos, Cuba.

Non-Supermarket

After an hour of searching the streets of Vedado, I finally found Galerias de Paseo and the supermercado that was promised to be inside. I walked up and down the aisles past sparsely stocked shelves stopping every few moments to examine a product. I picked up a bag of sugar that sat next to a section of powdered milk. I inspected a packet of beans and a can of tomato sauce. In the rear of the market was a freezer section, even more scant than the shelves, containing some frozen meat and fish. Compared to the rest of the store, twenty cases of orange soda juxtaposed across from a shelf of rum seemed like a bounty. The only indulgent offering seemed to be potato chips (imported from Spain) and a small section dedicated to gelatin. No Jello brand in these parts. By all indicators, this was “fancy” Cuba food. Not exactly the mega supermarket I’m used to state side, but this discovery was the reason I was here.

One of a few items in the extremely sparse Cuban market.

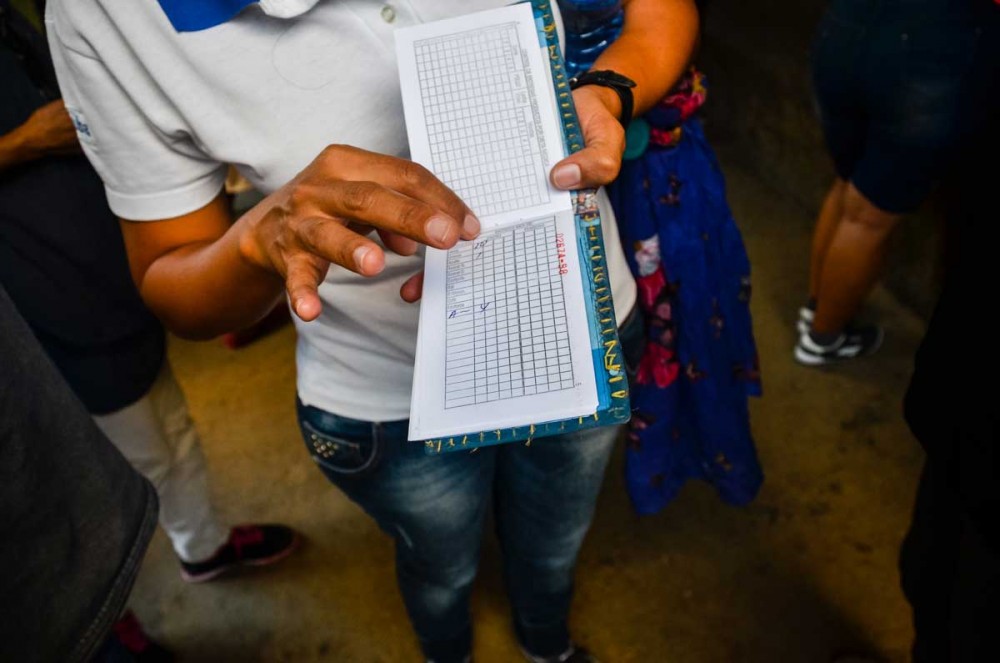

The Rations Commissary

The day before the market, I visited a government run libreta store. This is where most Cubans get there food and supplies. Not the supermercado. The libreta is the name for Cubans monthly rations, a system that was set up 60 years ago after the revolution to set allowances for the people. These products, like rice, beans, potatoes, light bulbs and toilet paper, have been sold for subsidized prices since the systems inception in 1962. The purchase process is accompanied by a Libreta de Abastecimiento. This “supplies booklet” is how shop clerks, and the government, keep track of who has received what. I’m not sure if this is obvious but these supplies are limited and strictly watched.

The rations booklet distributed to every Cuban household.

Between the commissary, supermarket and paladors, I was beginning to see the grim reality of Cuban life through Cuban food, or lack there of. This omission of creativity and standardization of cuisine was confusing at first. Then it hit me. In a country with rationed resources, experimentation with limited supply stifles the creativity of that particular medium. If I gave you just a few portions of pork, would you risk preparing a repugnant dish or stick with what you know? At that moment I understood the ramifications of communist control better than I had since landing. Armed with this new view I began to look back at my past few days wearing these newly found decoder glasses. What I saw was just how insulated Cubans have been from the progressive outside world that surrounds them. More importantly, how that isolation crafted a culture.

A look at Cuban cuisine from the locals market to the highest end palador .

Counter Consumerism

One of my most interesting moments of the isolated Cuban life was with Nancy, an architect and historian. We were in Trinidad, a small town five hours east of Havana that, due to limited access, has remained untouched since colonial times. We sat finishing up dinner in one of the newer paladors Trinidad boasts because of the recent tourist bus’ arriving each morning. It was a delicious stuffed pork belly BTW.

Streets of Trinidad

Pork Belly from one of Trinidad’s many Paladors

She explained how she wanted to purchase the rest of the building she lived in and turn it into a casa. A casa is a government allowed bed and breakfast often someone’s home. The most interesting part of the story was that this building abutted the only hotel in Trinidad. Michael and I explained to her that she could wait to be bought out by the hotel when they inevitably need to expand. We must have described this idea of supply and demand to her ten different ways but she still didn’t understand our point. Nancy was no fool. On the contrary, she was a highly educated and intelligent professional. Her hang up was cultural. Cuban’s are not accustomed to capitalism and therefore consumerism is non-existant. For a country where everyone makes the same amount of money, which is not a lot, the idea of accumulating wealth and spending it on luxury items is not only foreign but inconceivable. Part of this reality is the lack of places to spend this potential money. There is no Maserati dealership. Your neighbors don’t have things you covet. No one makes a lot of money, therefore no one has invested in businesses to spend that money. So, Nancy just doesn’t understand why waiting for a hotel to buy you out is an option if she can start renting rooms tomorrow.

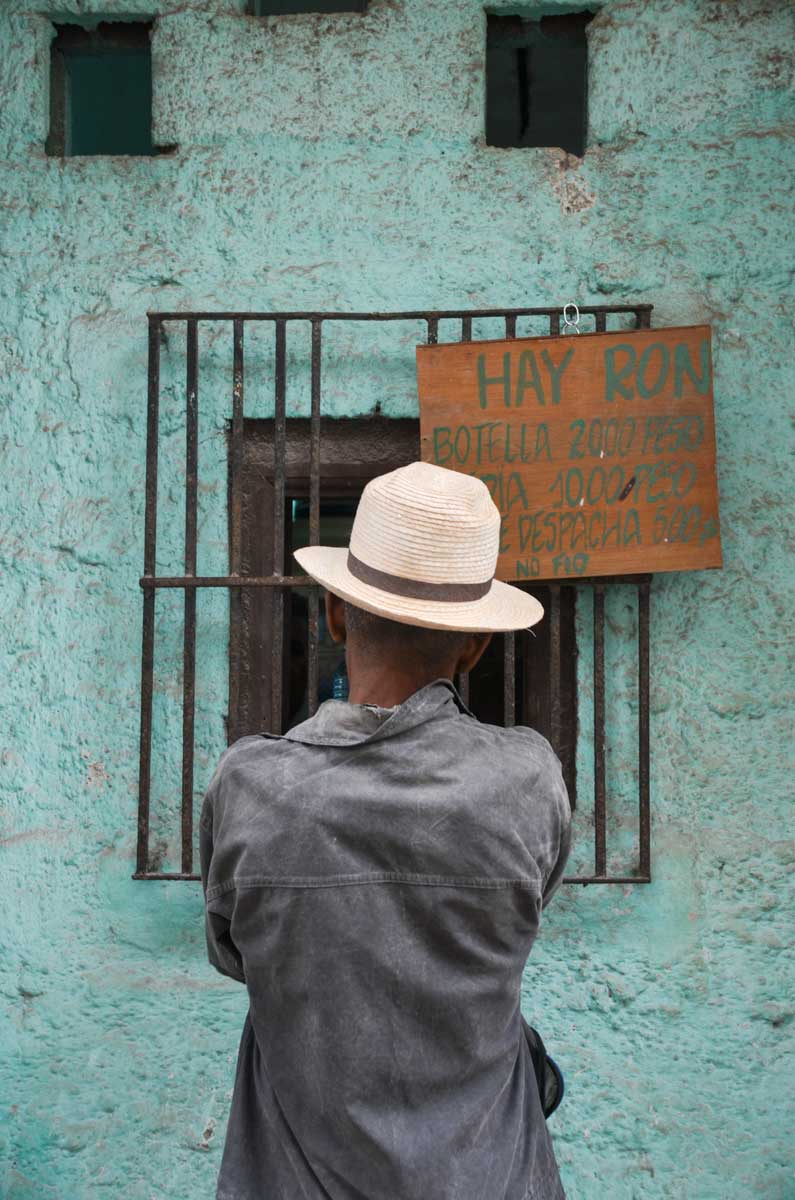

Cuban benefits vs Entreprenuerism vs Black Market

Everyone in Cuba is paid the same. They have few bills. The government pays their phone bill and gives them food at low cost. Sounds great right? Until you realize the wage barely allows them to buy the food they need. Add in, the food they need is capped by their ration card and you have a bit of a necessities scarcity. This usually leads humans, the determined and resilient species we are, to find other means of survival.

A street sweeper at sunrise on the Malecón.

Many of the locals take to other “business’” to augment this lack of basics. Using my “Nancy story” as a case in point, I don’t know if they even realize they are entrepreneurs. There’s a lot of unwritten things that go down in Cuba but none of them are done to become a “baller” and move up to a penthouse in the sky. As I looked closer, I realized just how much alternative business exists and again, wondered why.

Cubans are not in poverty but if you sit long enough with any of them they will express how tough life is.

Artists can sell art. Casas can rent rooms and houses can run restaurants. The government turns a blind eye. The black market runs deep. USB sticks are the back bone of a “pass around economy” containing the latest music, movies and news all being downloaded from one disk to the next. At best these two things make some Cubans a bit more well off than others. Although they still don’t have a place to spend the extra money. Maybe they buy more internet minutes or a fancy pair of lace stockings instead of the standard nude color. (Yes I did oddly see that world fashion trend in Cuba) Running a business or a black market hustle are still just slightly better ways of getting by. Cubans are not in poverty but if you sit long enough with any of them they will express how tough life is. In a lot of ways, it must be tougher than an Indian slum, or LA’s skid row. I say that from the perspective of “a state of rock bottom lets you know where you are”. Cubans seem to live someplace in between “I don’t have enough this month” and “the promise that it’s about to get better”. This is mostly the governments fault for being optimistically, propaganda-ish, confusing citizens into believing the future is bright when it’s really just a glowing cell phone screen. With this insight, I decided to turn back to food and find where it flourishes like these other businesses.

The Farm Bounty

So the paladors typically stay the course and don’t jump too far from the simple chicken and pork dishes. Ropa Vieja was the most complex thing I ate and that’s a Miami staple. I was treated to one meal that seemed oddly ostentatious but then I was informed why. When we pulled into the organic farm just outside Viñales it seemed like the outskirts of a recently painted tourist attraction. A short climb up a dirt path revealed one of the most magnificent views of the whole trip. I was on a bluff. In the distance, the Sierra de Los Organos mountains. were laid out before my eyes. Refocusing on the foreground, terraced gardens cascaded down the hill filled with a bounty of every fruit and vegetable imaginable.

Panoramic view of an organic farm outside the town of Viñales.

When we sat down we were treated to a seemingly endless 13-course lunch. Veggies, meat and the craziest flan cakes all dropped on the table over a 2-hour throw down. This was the most food I had seen my entire time in Cuba. As it turned out, this oasis had a very directed mission. The bounty was a result of their ability to grow it all themselves on the farm. More ingenious, the feast always produced leftovers which were distributed to the village residents. This explains why they could be so brazen with so much food. Simply put, the rest of the paladors didn’t serve what they didn’t have. Don’t get me wrong the cuts of meat, even simply prepared, were deliciously tasty due to the lack of chemical pesticides and hormones both in the animals and in their feed but the farm food was immeasurable better than even my favorite Havana palador experience. As I compared these meals and recalled the rest of what I had absorbed, the food again proves a great map to understanding the culture.

Slow Change Fast

As the trip came to a close I reflected on my journey and education. There’s a lot of foreign things about Cuba but there’s also a lot of familiar humanity. Despite all the old control, new rules and state side media coverage sensationalizing Cuba, it was obvious they have a long way to go to reintegrate into a world that’s 60 years ahead of them. The most significant, and somewhat overlooked, is a current rule held by the Cuban government that has been spoken about very little, if perhaps not at all, in the media. The Cuban government must own 51% of any business foreign or domestic. Until this is changed I don’t think Starwood, McDonald’s or Maytag are racing to give up the controlling share of their corporations to a stalwart communist regime passing themselves off as a newly progressive government.

Had I been more observant in that moment, it wouldn’t have taken me the rest of the trip to answer the question I asked myself.

Last Bites

Sitting at the counter in that tiny Havana cafe, I popped the last bite of my American influenced Cubano into my mouth, I pondered the irony of the sandwich as it relates to the last 100 years of Cuban history leading up to the recent changes between this country and my own. Had I been more observant in that moment, it wouldn’t have taken me the rest of the trip to answer the question I asked myself. Cuba is both a paradise and a prison. Its people are warm, loving and hard working. Their government has cared for them like stern parents. Over the next half decade I’m very curious to see if when the shackles are unlocked will this paradise thrive or, like a delicate flower, does the onslaught of consumerism and modernity wilt the paradise to death.